|

7. Towards a Settlement of the Gunyochi Problem

By far the most significant crack in the islandwide gunyochi struggle occurred in the Henoko district of Kushi Village. On 28th December 1956, in negotiations with the OED, landowners voluntarily signed contracts for 628-acres of uncultivated (genya and sanrin) land to be transformed into Henoko Naval Ordnance Depot[1] and the initial phase of US Marine Corps Camp Schwab.[2] Legally, these lands were acquired, as the Price Report had suggested in the case of land required indefinitely, under a 'fee title' or 'simple title.'[3] This was a variant of the hated lump-sum payment, but one that now, as Toma had suggested, left title and ownership clearly with the landowner and as such did away with any suggestion of permanent acquisition. On 23rd February 1957, CA Ordinance No. 164, 'United States Land Acquisition Programme (Beigasshukoku tochi shuyorei ni tsuite),' was issued, abolishing CA Ordinance No. 109, and clarifying three new types of estate.[4] In the Kushi area the initial lands acquired by the OED via 'fee title' was now officially defined as 'determinable estate.'[5] When the OED returned to Kushi in July of 1957 to acquire more lands for the Camp Schwab Training Area a 'leasehold' estate was also offered. This gave the OED a maximum five-year ownership period with rentals paid at "specified intervals."[6] The threat of forced land seizure was evident in this law, as in the complimentary CA Ordinance No. 171, 'Authority to Enter Upon Lands for Investigation and/or Survey Purposes (Tochi chosa oyobi sokuryo no tame no tachiiri kengen ni tsuite)'[7] but with increases in voluntary lease signing there was less need of Draconian measures. Individuals and groups associated with the yongensoku cause castigated local landowners for caving in to USCAR, but Kushi Mayor Higa Keiko[8] and community leaders defended their decision as being a rational response to economic conditions.[9] In November, USCAR took possession of about 21,450-acres of former GOJ land in the north of Okinawa for the Marine Corps Northern Training Area (now Jungle Warfare Training Centre).[10]

USCAR was no more enthusiastic about continued battle with landowners than the latter were resisting US policy indefinitely without any stable income. Kushi was first to back down, for its trouble receiving a barrage of criticism, yet there was some hypocrisy in the opposition's stance. Once base development in Henoko got underway traders and entrepreneurs from all over Okinawa recognised a business opportunity and descended. As US Marines arrived[11] restaurants, bars, and night-clubs sprang up. Henoko had not perhaps as sophisticated a military entertainment area as Koza, but its economic contribution was nonetheless attractive. In Kin, while some anger persisted, there was a grudging respect for and envy at Kushi's decision. Assembly members from Kin and Ginoza visited Henoko regularly to observe activities first hand.[12] There were conflicting opinions in Kin. While there was still allegiance to the yongensoku and the idea that bases must be resisted "so that children are not endangered,"[13] it was also argued that locals had been denied access to forest, lived with an ever-present threat of danger, yet received nothing of economic merit. This unpalatable reality was summed up by two expressions: "In Kin shells are falling, but not the dollars," and "troops train in Kin, but go to Koza and Henoko for fun."[14] Through public meetings at village and community level consensus was reached that the municipality and private landowners should accept new land expropriations.[15] This is described as kuju ni michita sentaku, or "having no alternative but make a bitter, distressing choice."[16]

For its part, and without compromising the military mission, the USG sought to eradicate impediments to good relations with Okinawa's landowners. The superficial Executive Order 10713,[17] issued by US President Eisenhower in June 1957, gave more authority to the GRI, but made no qualitative adjustment to what was a solid military administration.[18] More satisfying was a process of negotiations between the USG and the GRI which led to the announcement that Washington was seriously reconsidering its lump-sum ('determinable estate') policy on 11th April 1958.[19] A five-person group of Okinawans, led by the Speaker of the Ryukyu Rippoin Asato Tsumichiyo,[20] visited the US for talks from June through to July. So fruitful were these discussions that a US-Ryukyu Joint Declaration (Ryukyu retto gyosei shuseki ikko no Beikoku homon ni tsuite no kyodo seimei) was issued on 7th July in which the USG finally admitted that the lump-sum payment policy was abhorrent to most landowners and should go, and the Okinawan side recognised that the US needed its bases in Okinawa to defend the free world from Communism.[21] Both sides agreed to tie up loose ends in a series of negotiations to take place in Okinawa thereafter. The genchi sessho, or 'on-the-spot negotiations,' began at the Harbour View Club in Naha on 11th August. The USG and GRI each selected 12 representatives for the full US-Ryukyu committee[22] which then split into three specialised groups to iron out minute differences. By December most of the remaining land-related problems had been resolved, but not all.

For Kin particularly, but also other municipalities that suffered loss of a large amount of land seized during wartime and retained by the US military in the postwar period, the issue of pre-MTPJ compensation was of great importance.[23] It turned out to be complex. In short,[24] whilst the USG had no financial obligation for pre-MTPJ land use, it took some responsibility by making payments for the period 1st July 1950 to 28th April 1952, if at unacceptably low levels in the view of the landowners. The issue of what constituted fair rentals for the period, and who was technically liable, if at all, dragged on. Additionally, there was the problem of pre-1st July 1950 rentals that landowners argued was at the very least Tokyo's responsibility if not the USG's, and the complicated issue of compensation for personal injuries and appurtenances[25] for the whole pre-MTPJ period. The Tochiren head Kuwae Choko and Ryukyu Rippoin Member Oyama Chojo had pushed the issue in Washington in 1955 without success. Three years on the situation was different. The GOJ was now getting involved on the landowner's behalf and had the financial muscle to offer practical assistance. Firstly, the Nampo Doho Engokai (NDE) had been established with GOJ and private funding in September 1957 as a non-governmental organisation with one eye firmly focused on Okinawa. On the advice of Suzuki Gengo of the GOJ's Okurasho (Finance Ministry) the NDE secured the services of Washington attorney Noel Hemmendinger[26] on a $10,000 annual retainer.[27] Hemmendinger met with Kuwae and agreed to advocate for the landowners in pressing their pre-MTPJ claims to the US State and Defence Departments. Hemmendinger submitted his petition and brief to both departments on 19th December 1958.[28]

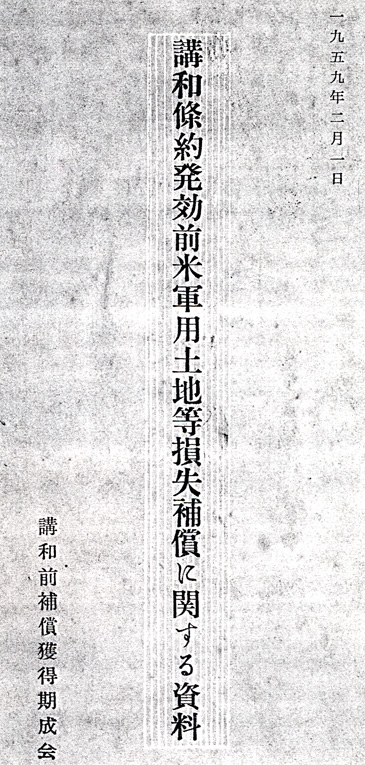

While not accepting liability for the pre-MTPJ period, the GOJ did try to help the Okinawan landowners by authorising a mimaikin, or solatium, of 1,000,000,000-yen (a shade above $2.8-million) from the fiscal 1956 budget[29] on the proviso that it be paid back at such time as the USG took responsibility. Although the mimaikin was useful it barely scratched the surface of the compensation problem. Early estimates put Kin's pre-MTPJ claim alone at a little over $900,000.[30] Finally, on 5th December 1960, High Commissioner of the Ryukyu Islands (HiCOM) General Donald P. Booth announced that he was establishing a joint US-Ryukyu committee (Kowamae Hosho Ryu-Bei Godo Iinkai) to resolve the issue of rent payments and compensation from 1st July 1950 to 27th April 1952.[31] His successor Paul W. Caraway approved a plan in August 1961 to settle this with a $2-million payment.[32] Caraway set up a second US-Ryukyu committee in April 1961 to examine pre-July 1950 compensation issues. In a letter sent to new US President John F. Kennedy by the Kin Assembly Chairman Nakama Kiichiro, Kin Mayor Ginoza Tatsuo, and the Military Land Committee Head Okuma Seitoku, in March 1961, all urged prompt attention be given to the issue in the upcoming 87th session of Congress since the total $1.1-million Kin was asking affected 88% of the village's families.[33] Based on figures from the Kowa Hakko mae Sonshitsu Hosho Kakutoku Kiseikai,[34] or 'Okinawan Association to Acquire Compensation for Damage Prior to the Peace Treaty,' the initial claim for Okinawa's shi-cho-son for the entire pre-MTPJ period was $42.8-million.[35] Readjustment was made after HiCOM Caraway's announcement that there would be a full and fair investigation, bringing the Okinawan claim down to $26.2-million.[36] The committee went to and fro on what the valuation should be, ending up with a figure of $21.8-million covering twenty-one separate damage classes when the final report was sent to the USG for consideration in October 1962.[37] Finally, on 17th October 1966, US President Lyndon B. Johnson formally signed a bill authorising an ex gratia payment of $22-million.[38] HiCOM Ordinance No. 60, 'Settlement of Ryukyuan Pretreaty Claims,' issued on 10th January 1967, explained that the funds would be deposited in a non-interest bearing account at Ryukyu Ginko.[39] The last element of the land problem was that of mokunin shiyochi, or lands used with tacit approval. This was an issue that reared up in the mid-1960's.

[1] This facility, also known simply as Henoko Ordnance Depot (FAC 6010), occupies a 1.2 million sq. metres of land across the Henoko and Futami subdistricts (now within Nago City). Okinawa-ken, Somubu, Chiji Koshitsu, Kichi Taisakushitsu, Okinawa no Beigun kichi (Naha: Somubu, Chiji Koshitsu, Kichi Taisakushitsu, 1998), 40-41.

[2] Okinawa Times, 21st December 1956. Camp Schwab (FAC 6009) is a single facility occupying 20.6 million sq. metres of land (in the Toyohara, Kushi, Henoko, Kyoda, Sukuta, and Yofuke districts of Nago, and the Matsuda District of Ginoza Village), but was constructed in three parts. The first, in 1956, was simply known as 'Camp Schwab.' The second, in 1957, was the 'Camp Schwab Training Area.' The third, in 1959, was the 'Camp Schwab LST Anchoring Facility.' Okinawa no Beigun kichi, 34-35. On the Henoko landowners voluntarily signing contracts see USCAR, Civil Affairs Activities in the Ryukyu Islands for the Period ending 31st March 1957, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Naha: USCAR, 1957), 66.

[3] US Congress, House of Representatives, Report of a Special Subcommittee of the Armed Services Committee, House of Representatives, Ibid., 7664. The complexities of the "fee title" are discussed in Miyasato Seigen, Amerika no Okinawa tochi, 105, and at some length in the local newspapers. See Okinawa Times on 21st and 22nd December, and the 30th December edition of the Ryukyu Shimpo.

[4] CA Ordinance No. 164, 'United States Land Acquisition Programme,' 23rd February 1957. Laws and Regulations During the US Administration of Okinawa, 489-498.

[5] Ibid., 489-490. Payment was made in a lump-sum equivalent to 16.6 year's worth of rentals based on the appraised rate for FY 1955.

[6] Ibid., 490. The third kind of estate being 'easement,' applied for short-term land requirements.

[7] CA Ordinance No. 171, ''Authority to Enter Upon Lands for Investigation and/or Survey Purposes,' 25th June 1957. Laws and Regulations During the US Administration of Okinawa, 550.

[8] Okinawa Shakai Taishuto member Higa had been narrowly beaten by Shinzato Ginzo in the March 1956 Legislative elections. He was to run again as an independent in the March 1958 elections, this time being beaten more comfortably by Tsukayama Choshin. Nakano Yoshio, editor., Sengo shiryo Okinawa (Tokyo: Nihon Hyoron Sha, 1969), 749.

[9] USCAR, Civil Affairs Activities in the Ryukyu Islands for the Period ending 31st March 1957, Vol. 5, No. 1 (Naha: USCAR, 1957), 66.

[10] This had been predominantly protected national forestland. USCAR, Civil Affairs Activities in the Ryukyu Islands for the Period ending 31st March 1958, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Naha: USCAR, 1958), 29.

[11] The USG promised to remove all combat forces from Japan, with the 3rd Marine Division relocated to Okinawa. Between 1st July 1957 and 15th October 1957, the number of forces in Japan had dropped from 100,000 to 82,000, many of whom transferred to Okinawa. 'Memorandum From the Director of Northeast Asian Affairs (Parsons) to the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs (Robertson),' 10th December 1957. US DoS, FRUS, 1955-1957, Volume 23, Part 1: Japan (Washington, DC: US GPO, 1991), 543. The 1st Marine Air Wing remained in Japan proper.

[12] Kin-cho to kichi, 32.

[14] "Kin ni wa dan ga ochiru ga, doru ga ochinai," and "Enshu wa Kin de yari, yukyo wa Henoko to Koza." Ibid. A variation on the first expression was "bakudan wa Kin ni otoshi doru wa chubu ni otoshiteiru (the bombs are dropping in Kin while all the dollars are falling in Koza [and other parts of central Okinawa])," Kin-cho Gunyochito Jinushikai, Kin-cho Gunyochito Jinushikai 40 shunen kinenshi (Kin: Kin-cho Gunyochito Jinushikai Henshuin, 1993), 29.

[15] For an interesting discussion of Kin's thinking on new land acquisitions for a Marine Corps base see Okinawa Taimusu, 9th October 1957.

[16] Kin-cho to kichi, 33.

[17] Executive Order 10173, 'Providing for the Administration of the Ryukyu Islands,' issued 5th June 1957. US DoS, Department of State Bulletin 941 (8th July 1957), 55-58.

[18] A fact recognised by the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB) of the National Security Council in the Progress Report NSC 5516/1, dated 14th October 1957. This report stressed that "the Ryukyus are the only place in world where the [US] can be charged with colonialism," and that the Executive Order was simply "no substitute" for a proper policy paper. 'Memorandum From the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs (Robertson) to the Secretary of State,' 15th October 1957. US DoS, FRUS, 1955-1957, Volume 23, Part 1: Japan (Washington, DC: US GPO, 1991), 513-514.

[19] Ryukyu Shimpo, 12th April 1958. 'Determinable estate' was finally abolished under High Commissioner Ordinance No. 18, 'Acquisition of Interim Leasehold Interests,' 13th January 1959. Laws and Regulations During the US Administration of Okinawa, 651-654.

[20] Along with Tochiren head Kuwae, the Shi-cho-son Mayors Association Chairman Togeru, GRI Legal Affairs Bureau head Akamine, and Assembly Member Yogi. Chief Executive Toma Jugo joined the group in Washington for the testimony to Congress. Okinawa Taimusu, 10th June 1958. For a good account of the second Washington trip see Kuwae Choko, Tsuchi ga aru, ashita ga aru: Kuwae Choko kaikoroku, 125-137.

[21] Ryukyu retto gyosei shuseki ikko no Beikoku homon ni tsuite no kyodo seimei. Ryukyu Shimpo, 8th July 1958. Just 23 days later USCAR announced that the lump-sum payment would be abolished.

[22] For a list of the GRI-Okinawan representatives (mostly the same old faces) and opinions see Ryukyu Shimpo, 9th August 1958. On the first meeting see Okinawa Taimusu, 12th August 1958, on the second meeting see Ryukyu Shimpo, 9th September 1958, on the third meeting see Ryukyu Shimpo, 7th October 1958, and on the fourth meeting see Okinawa Taimusu, 14th October 1958. On the wrap-up of the genchi sessho see Ryukyu Shimpo, 4th November 1958. All the above articles make for interesting reading. For a concise overview see Miyasato Seigen, Amerika no Okinawa tochi, 132-133.

[23] In examining documents from the occupation period retained by Kin, the current writer estimates a significant quantity of the total, perhaps one-quarter, falls in the category of Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho ni kansuru (Related to Compensation for Damages in the Pre-MTPJ Period).

[24] Since there has been quite lengthy discussion of land laws and the USG's legal obligations toward the Okinawan landowners earlier in this chapter.

[25] Also known as 'accessories' or 'improvements,' this category related to built structures on the land: such as tombs, wells, stone walls, and water tanks, and to agricultural crops, trees, fruit bushes, and the like, that had also been lost by the landowner at the time of seizure. For a breakdown of the various categories and the amount demanded by each municipality see Kowa Hakko mae Sonshitsu Hosho Kakutoku Kiseikai (The Okinawa Association to Acquire Compensation for Damages Prior to Peace Treaty [sic]), 'Tainichi heiwa joyaku mae sonshitsu hosho seikyokaku (Claimed Amount for Damage and Loss Prior Peace Treaty to Japan [sic]),' 3rd May 1961. RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho seikyosho: sono ta (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[26] Who had previously served with the US Department of State's Office of Northeast Asian Affairs in drafting the property and claims sections of the MTPJ. For an interesting account of the Okinawa land problem see L. Eve Armentrout Ma, 'The Explosive Nature of Okinawa's "Land Issue" or "Base Issue," 1945-1977: A Dilemma of United States Military Policy,' The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 1, (1992). Ma is the only person in the recollection of the current writer to have interviewed Hemmendinger on his role with the Okinawan pre-MTPJ claims.

[27] Kuwae Choko, Tsuchi ga aru, ashita ga aru: Kuwae Choko kaikoroku, 132. In the article above (footnote 65, page 451) L. Eve Armentrout Ma states that Hemmendinger later received a "modest percentage (less than 1 percent) of the actual award." In the case of compensation paid out by the USG for the period 1st July 1950 to 27th April 1952 in Kin Village, however, documentation indicates that the percentage extracted from the award for lawyer's fees was closer to 2% (1.8% or 1.9%). See form: Kin-son, 'Kowa hakkomae sonshitsu hosho no bengoshi hoshu bishubo (1950/7/1 - 1952/4/27 made no kikan),' 22nd March 1963. RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho kankei shorui (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[28] For a Japanese translation of Hemmendinger's petition and brief see the 116-page: Kowamae Hosho Kakutoku Kiseikai, Kowa joyaku hakko mae Beigunyo tochito sonshitsu hosho ni kansuru shiryo (1st February 1959). RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho kankei shorui (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[29] The mimaikin payment, known as the Okinawa kankei tokubetsu sochihi (Okinawa-related Special Measures Expenditure) was 1,100,000,000-yen in total. For a breakdown see Sengo Okinawa keizaishi, 558-559.

[30] Kin is listed as having 1,420 claimants (6,043 claims) and a demand for 108,861,328.00 B-yen. Okinawa Gunyo Tochito Mimaikin Shori Iinkai, 'Okinawa kankei tokubetsu sochihi no shishutsu ni tsuite,' 2nd May 1957 (a 7-page document outlining the terms of the GOJ mimaikin, the method of application, and a breakdown by shi-cho-son of claimants and claim figures). FT: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho ni kansuru tojiri (Kin-son Yakusho). RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho seikyosho: Gunyochi kankei shorui tojiri kankei (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[31] Ryukyu Shimpo, 6th December 1960. There were 6 Okinawan representatives, Kuwae Choko (now an Assembly Member representing the recently-formed Okinawa Jiyu Minshuto, or Okinawa Liberal Democratic Party), being the most recognisable in a group consisting of two legal experts, one mayor, a municipal assembly member, and the new Tochiren deputy-chairman.

[32] Caraway stating that for this period the USG had already paid so $1,136,000 to the landowners. Ryukyu Shimpo, 29th August 1961. According to USCAR reports, by 1st April 1962, owners of 67,765 tracts of land had been paid an additional $1,243,981 in rentals for the July 1950-April 1952 period, and an unspecified percentage of a $3.8-million fund for damages and appurtenances over the same period. USCAR, Civil Administration of the Ryukyu Islands Report for the Period 1st April 1961 to 30th June 1962, Vol. 10 (Naha: HiCOM, 1962), 86.

[33] 'Letter to the Honourable President of the United States. Subject: Request for Passage of Bills Authorising the Government of the Ryukyu Islands to Make a Disbursement for Compensation Payable for Damage to or Loss of Private Properties as Used by the United States Armed Forces and for Personal Death or Injury Suffered by the Ryukyuan Individuals as Caused by the US Armed Forces Personnel Before the Entry into Force of the Japanese Peace Treaty,' dated March 1961, from Nakama Kiichiro, Ginoza Tatsuo, and Okuma Seitoku. FT: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho ni kansuru tojiri (Kin-son Yakusho). RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho seikyosho: Gunyochi kankei shorui tojiri kankei (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[34] Combining the resources of the Tochiren, and the municipal and mayoral land committees.

[35] Kowa Hakko mae Sonshitsu Hosho Kakutoku Kiseikai (The Okinawa Association to Acquire Compensation for Damages Prior to Peace Treaty [sic]), 'Tainichi heiwa joyaku mae sonshitsu hosho seikyokaku (Claimed Amount for Damage and Loss Prior Peace Treaty to Japan [sic]),' 3rd May 1961. RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho seikyosho: sono ta (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[36] Kowa Hakko mae Sonshitsu Hosho Kakutoku Kiseikai (The Okinawa Association to Acquire Compensation for Damages Prior to Peace Treaty [sic]), 'Tainichi heiwa joyaku mae sonshitsu hosho seikyokaku (Claimed Amount for Damage and Loss of Prior Peace Treaty to Japan [sic]),' 20th May 1961. RG: Kowa mae sonshitsu hosho seikyosho: sono ta (Kikaku Kaihatsuka). Kin-cho Shihensan.

[37] Ryukyu Shimpo, 16th October 1962.

[38] Ryukyu Shimpo, 18th October 1966.

[39] HiCOM Ordinance No. 60, 'Settlement of Ryukyuan Pretreaty Claims,' on 10th January 1967. Laws and Regulations During the US Administration of Okinawa, 906-908.

|

|